“It’s on America’s tortured brow / that Mickey Mouse has grown up a cow. Now the workers have struck for fame, 'cause Lennon's on sale again.”

Bowie distills what makes Mickey so fascinating—he’s more than just a cartoon. He’s a cultural chameleon, shifting from mischievous trickster to patriotic emblem to corporate monolith, only to be reclaimed by artists and countercultural movements as a critique of the very system he came to represent.

From Steamboat Willie’s rebellious charm to his role as a mascot of corporate power, and later, an ironic and subversive icon wielded by punk rockers, street artists, and dissidents, Mickey’s evolution tells a story far bigger than himself.

But how did a simple cartoon mouse become such a contested, multivalent symbol? And what does his constant reinvention say about America as a whole?

A Personal Reflection

For me, Mickey Mouse was never just a character—he was always there, a fixture of my cultural DNA. Like most American children, I can’t remember the first time I saw him.

The first Mickey I knew wasn’t defined by personality or story. He was a symbol—three simple, powerful circles. But I do remember the first time I met him, or at least a costumed version of him at Disneyland. Overwhelmed, I burst into tears.

Years later, in 2013, I found myself working on the Mickey Mouse Shorts at Disney—an effort to recapture the character’s original magic. By then, I had worked on plenty of fresh, contemporary animation projects, but nothing got a bigger reaction than the fact that I was working on Mickey Mouse cartoons. To this day, my parents have never been prouder.

Restoring Mickey’s original personality, look, and charm required a deep dive into research. We had access to the Disney archives—a vast collection of historical artwork, concept sketches, and animation. As I pored over the material, I was struck by just how much Mickey had evolved.

A Trickster with an Edge

Mickey Mouse started as a mischievous, rebellious trickster in the late 1920s—a subversive figure who connected with audiences struggling through the Great Depression. He was scrappy, resourceful, and full of energy, a reflection of the American spirit in tough times.

John Canemaker, writing in The New York Times in 1995, captured the raw, unpolished nature of this early Mickey:

“A white mask on a black circular head with pie-shaped eyes, two smaller ear-circles and two-button short pants on a round black body. But Mickey was also a grungy, goggle-eyed, long-snouted ratlike creature, with tubular arms and legs, no gloves, no shoes and no class.”

This scrappy, almost anarchic version of Mickey felt alive—his movements were wild, his expressions elastic, and his personality bursting with mischief.

But as Disney’s popularity grew, his rough edges were smoothed over. His design became rounder, more human-like, and his once-relatable charm faded into a blank slate onto which anything could be projected. This shift made him ripe for reinvention—not just by Disney, but by the culture at large.

Reinvention Beyond Disney: Mickey as Folk Art

An early, unexpected example of this reinvention can be found at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C. The Hopi Mickey Mouse kachina doll, crafted in the 1930s, merges traditional Hopi religious symbolism with Mickey’s unmistakable form—an early instance of appropriation and reinterpretation.

Kachina dolls represent sacred spirits, and Mickey’s inclusion in this tradition reflects his rapid rise as an American folk figure. Long before he became a corporate icon or countercultural symbol, he was already being reshaped beyond Disney’s control, proving his role as a cultural chameleon.

Mickey Goes to War: A Symbol of Patriotism

By World War II, Mickey had become a fully-fledged nationalistic symbol. Disney Studios backed the war effort with propaganda films, military training videos, and over 1,200 unit insignias featuring the mouse.

The 1942 short Out of the Frying Pan Into the Firing Line featured Minnie Mouse urging households to donate bacon grease for explosives. Perhaps the strangest example was the Mickey Mouse gas mask, designed in 1942 to make chemical warfare less frightening for children. A collaboration between the U.S. Army and the Sun Rubber Company, it featured Mickey’s signature ears and a red snout.

The eerie contrast between its playful design and the grim reality of war underscored the tension between innocence and propaganda.

By war’s end, Mickey was more than a cartoon—he was a national emblem. But his patriotic, sanitized image came at a cost, smoothing away the rebellious spark that had once defined him.

Creativity vs. Commerce: The Battle for Artistic Freedom

One of the strangest, most overlooked chapters in Mickey Mouse’s evolution came in 1955, when he starred in a series of Nash Rambler car commercials.

Designed by Tom Oreb, a pioneer of mid-century modern animation, Mickey underwent a radical transformation. Oreb streamlined him into a sleek, angular figure—his typically rounded form replaced with sharp edges and a bold graphic sensibility.

It was a dramatic reinvention, placing Mickey within the modernist aesthetics of the atomic age and the rapidly shifting cultural landscape of the time.

The commercials aired, and the backlash was immediate—but not for the reason one might expect. Walt Disney wasn’t outraged that Mickey was being used to sell cars. He was furious over the modernist redesign.

A young fan, who had previously warned Walt to stay away from modern art because it was “Communistic,” wrote him a letter:

"I'm disappointed Walt. I never thought you'd succumb. What happened to you?"

Disney banned further experimentation with Mickey. From that moment on, he would be locked into his role as a corporate mascot, stripped of artistic reinvention.

But if Mickey was no longer evolving within Disney, artists outside the studio were more than ready to take matters into their own hands.

The Politics of Mickey Mouse

Meanwhile, Walt Disney’s growing political involvement fueled the backlash. In 1947, he testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee, accusing former employees of communist ties. By 1956, Disney Studios produced animated ads for Eisenhower’s campaign, while Walt’s studio cart displayed bumper stickers for conservative candidates like Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon.

Mickey Mouse, once a mischievous figure, was now tied to Disney’s increasingly political and patriotic brand. The counterculture responded.

Mickey’s Dark Reflection: The Wild World of Rat Fink

One of the first and most striking countercultural responses to Mickey came in 1958 with Ed “Big Daddy” Roth’s creation of Rat Fink. Conceived as Mickey’s grotesque, anarchic opposite, Rat Fink was a bulging-eyed, snaggle-toothed, slobbering rat who embodied the rebellious, hot rod-loving spirit of underground car culture.

Unlike Mickey, the corporate icon, Rat Fink was an outsider, a symbol of those who rejected the sanitized version of American life that Disney represented.

Rat Fink wasn’t an isolated phenomenon. The 1950s were an era of growing cultural rebellion. The Beats were questioning conformity, rock and roll was rattling the status quo, and underground movements were forming around everything from comic books to custom car culture.

Roth’s creation tapped into this restless energy—vulgar, weird, and unapologetically grotesque. He was the perfect response to a world that increasingly felt polished into something lifeless.

Rebel Ink

And he was just the beginning. Once Mickey had been locked into his role as a corporate logo, artists, musicians, and dissidents saw an opportunity. Over the next few decades, Mickey would mutate into something far more fascinating—sometimes beautiful, sometimes terrifying, but always a reflection of the culture around him.

This subversive streak first took shape in underground comics. Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman’s Mickey Rodent! strip in Mad #19 (1955) mocked Mickey as a washed-up, unshaven movie star, kicking off a tradition of rebellious portrayals.

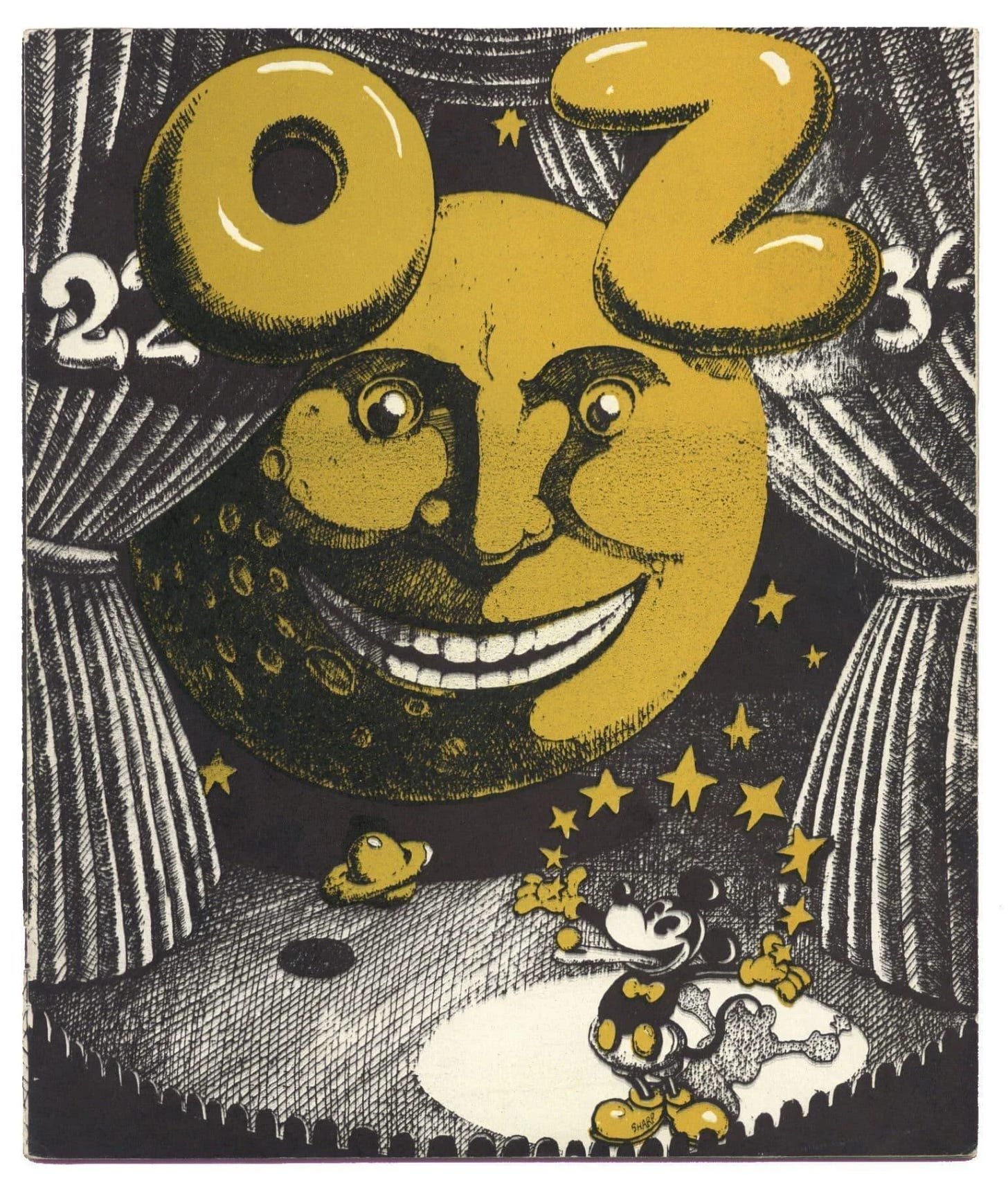

The satire escalated with OZ magazine’s controversial 1970 issue, featuring psychedelic, anarchic depictions of Mickey that contributed to Britain’s infamous 1971 obscenity trial.

Around the same time, Robert Armstrong’s Mickey Rat turned him into a sleazy, opportunistic figure, while underground artists like Robert Crumb and Moebius used the character to critique American commercialism and conformity.

While many of these underground critiques were driven by shock value, Art Spiegelman’s Maus stands out as a more complex and layered commentary. The Nazis, who saw Mickey Mouse as a symbol of American cultural influence, often compared Jews to vermin. Spiegelman subverts this propaganda trope by depicting Jews as mice, turning the comparison into a metaphor for power dynamics and dehumanization.

In doing so, he critiques both historical manipulation of cultural symbols and Mickey’s transformation from a symbol of innocence to a corporate entity caught in the web of global power and cultural critique.

Mickey Reborn: Artists Transform the Icon

Beyond comics, some of the most influential artists of the 20th century used Mickey Mouse to explore themes of commercialization, pop culture, and societal critique.

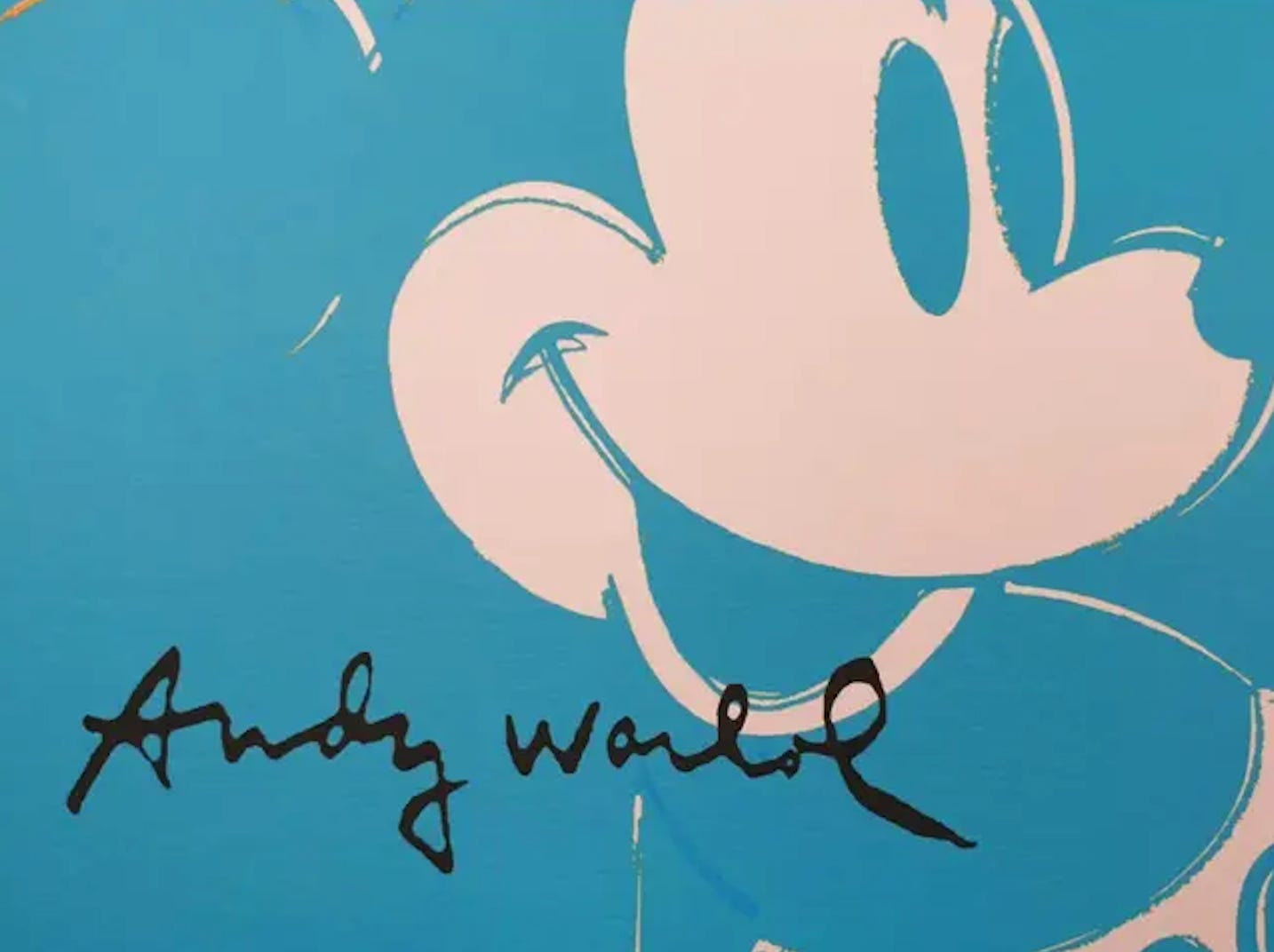

Andy Warhol’s signature screen prints elevated Mickey to fine art, blurring the lines between consumerism and high culture. Roy Lichtenstein deconstructed his image with Ben-Day dots, emphasizing the mechanical reproduction of pop icons.

Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, both deeply engaged with street culture and social activism, saw Mickey as a symbol of corporate dominance and cultural hegemony.

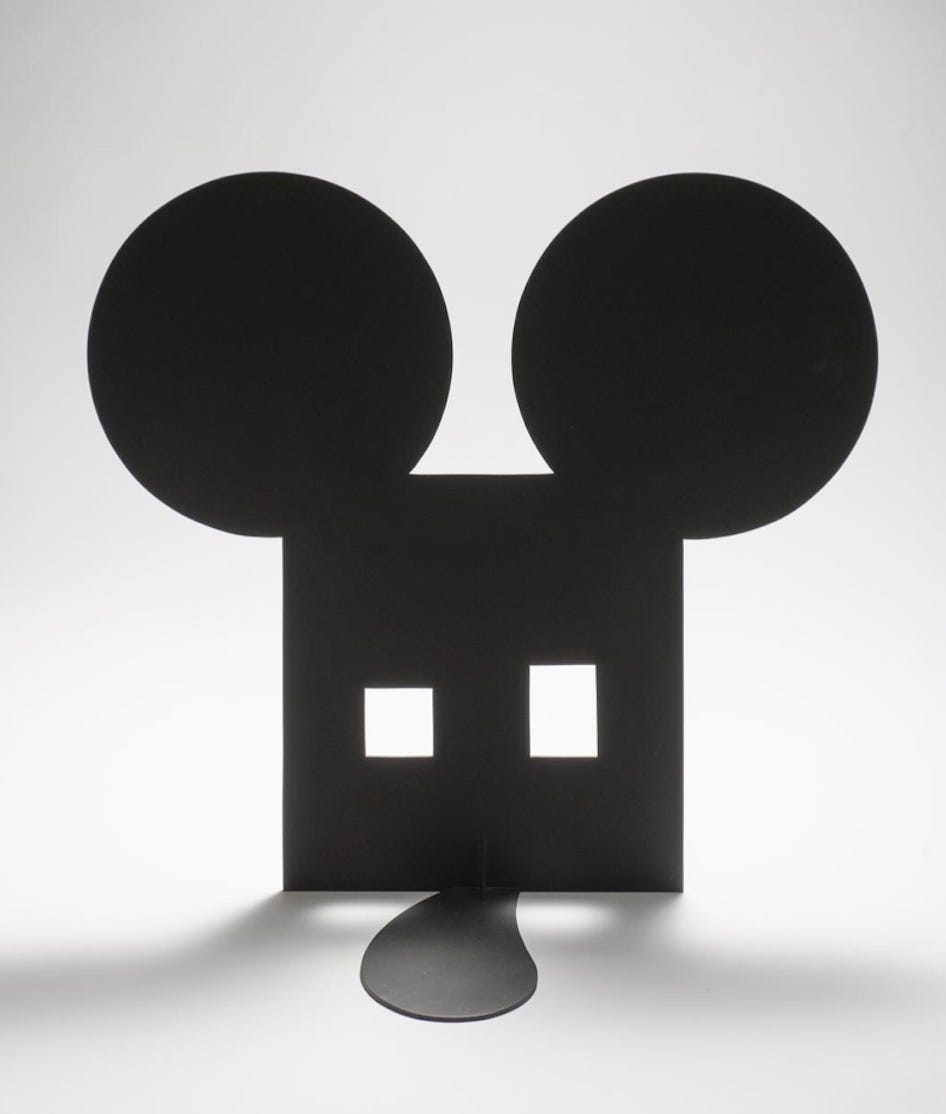

Claes Oldenburg stands out as one of the most intriguing artists to use Mickey Mouse as a muse. In his 1967 work Geometric Mouse, Oldenburg reimagines Mickey through a minimalist, sculptural lens, transforming the character into abstract geometric shapes. This stripped-down version of Mickey reflects the rise of a more commercialized, marketable culture, turning a beloved character into a simplified icon for mass consumption.

This artistic interrogation continues into the 21st century, most notably with Banksy’s 2011 Livin’ the Dream, in which he altered a Sunset Boulevard billboard to depict a drunken Mickey and a drug addled Minnie Mouse—an ironic commentary on the commercialization of beloved characters and the entertainment industry's grip on society.

A Critique of Power and Nationalism

Mickey’s image has also been subversively repurposed in animation and film, often as a critique of power and nationalism.

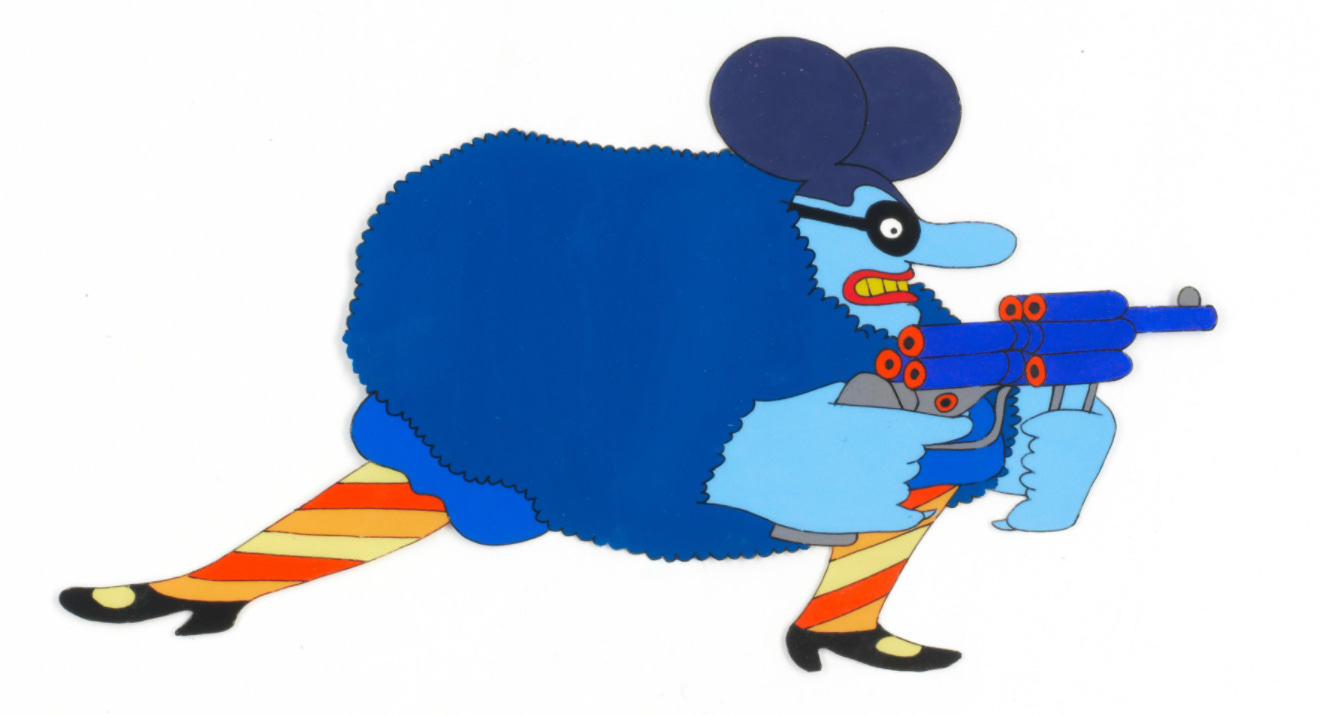

In Yellow Submarine (1968), the villainous Blue Meanies wear Mouseketeer-style caps, transforming Mickey’s cheerful image into a symbol of oppression.

A year later, animator Whitney Lee Savage—who contributed to the original Sesame Street—and artist Milton Glaser, creator of the iconic Dylan poster, created an animated short in which Mickey marches off to war in Vietnam, only to be instantly killed.

This stark anti-war statement cast Mickey as a blind nationalistic symbol, sending a sharp message to underground film screenings and anti-war gatherings.

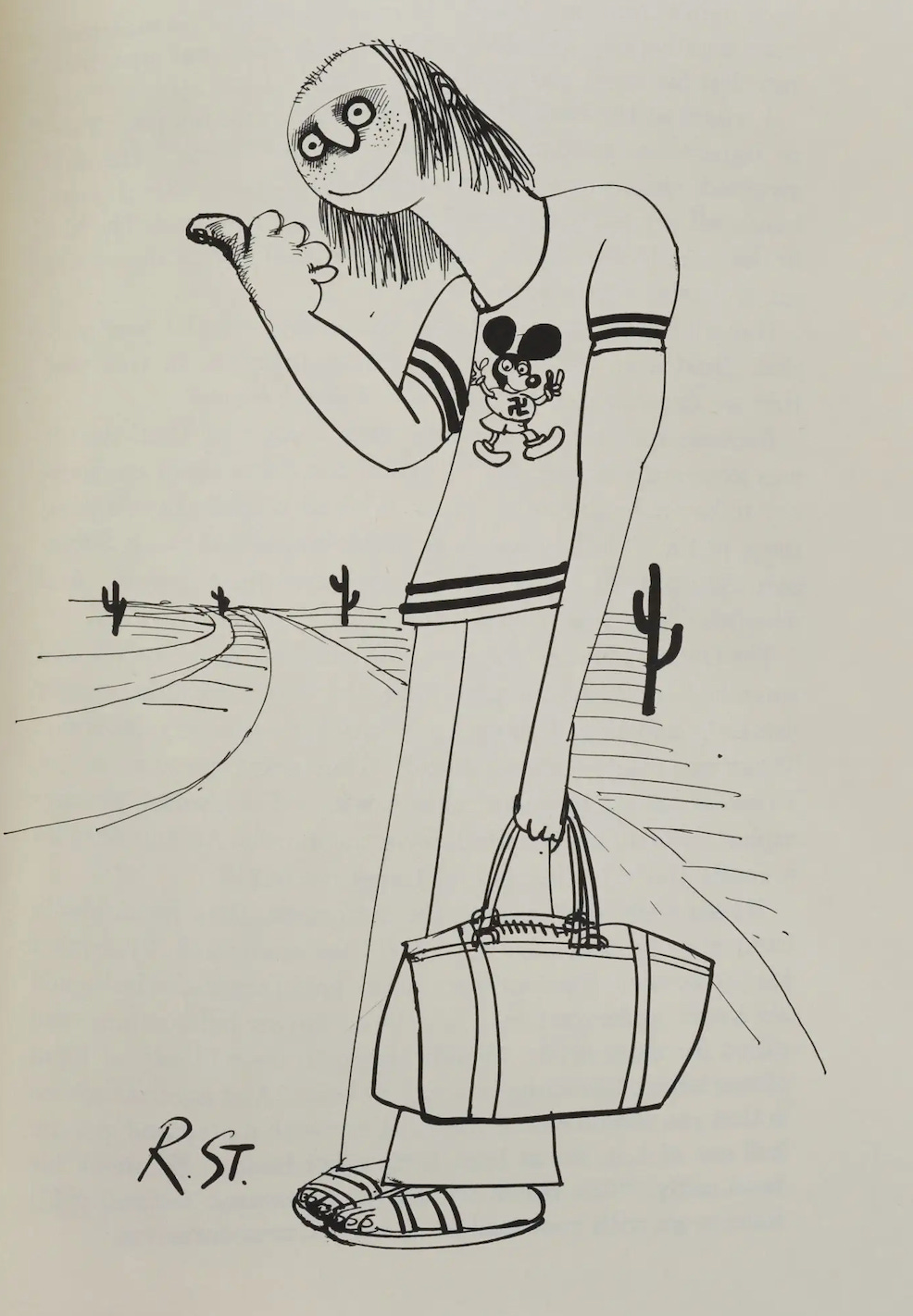

Illustrators like Saul Steinberg and Ralph Steadman also wielded Mickey’s image as a weapon of satire. Steinberg, known for his incisive visual commentary in The New Yorker, created Six Terrorists (1971), depicting a distorted, menacing Mickey as a warning against unchecked capitalism and cultural imperialism.

Steadman, best known for his Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971) illustrations, took a similarly provocative approach. One of the book’s most unsettling drawings features a hippie wearing a Mickey Mouse T-shirt with a swastika emblazoned on the chest—a stark commentary on the corruption of American ideals.

Love and Hate

Even artists who loved Mickey as a character expressed unease about his transformation into a corporate monolith.

Maurice Sendak, who grew up with the original mischievous version of Mickey, wove his influence into Where the Wild Things Are and In the Night Kitchen.

Yet, he also lamented the shift in Mickey’s character over time, once stating,

“I loved Mickey Mouse as a child, but I never cared for his long ears and big eyes when he became an icon.”

Punk, Pop, and a Mouse Reclaimed

Music provided yet another lens through which Mickey’s cultural meaning was examined.

In the 1970s, bands like the Ramones, Television, Patti Smith, the Sex Pistols, and the Clash reshaped music and culture by reclaiming discarded relics of the past.

The Ramones, in particular, embraced the unfashionable aesthetics of 1950s pop culture—bubblegum music, leather jackets, and even Mickey Mouse T-shirts.

For punks and new wavers, wearing Mickey wasn’t just nostalgia; it was a layered statement—mocking, reclaiming, and rejecting both corporate Mickey and the Sixties’ outright dismissal of him.

And then, there’s David Bowie’s Life on Mars?.

Of all the artists who have depicted Mickey, Bowie’s interpretation resonates the most. In the song, a young woman disillusioned with reality mourns what’s been lost:

“It’s on America’s tortured brow / that Mickey Mouse has grown up a cow.”

The scrappy, witty trickster had become dull, drained of his rebellious spirit. She isn’t angry—she’s sad.

Unlike many countercultural artists who portrayed Mickey with outright cynicism, Bowie’s take carries a sense of mourning—a lament for what had been lost.

His Mickey is both beloved and betrayed, a reflection of how so many of us feel about the character today. I share that sentiment. Having worked as an artist on Mickey Mouse Shorts, I’ve seen firsthand his potential for playfulness and reinvention. Yet, I also recognize how his image has been stretched, commercialized, and commodified to the point where he often feels more like a brand than a character.

Like Bowie, I view Mickey with both affection and frustration—torn between admiration for his legacy and disappointment in what he has become.

Mickey Mouse stands as one of the most significant icons of the modern era—not just because of his cultural ubiquity, but because he serves as a mirror to the American experience.

Over the decades, he has reflected the nation’s shifting ideals, dreams, and contradictions—at times embodying its optimism and creativity, at others revealing its commercial excesses and cultural tensions.

Whether as a symbol of joy and imagination or a representation of corporate power, Mickey’s evolution tells the complex, ever-changing, and deeply fascinating story of America—one that is by turns inspiring, turbulent, and unsettling, yet always captivating.